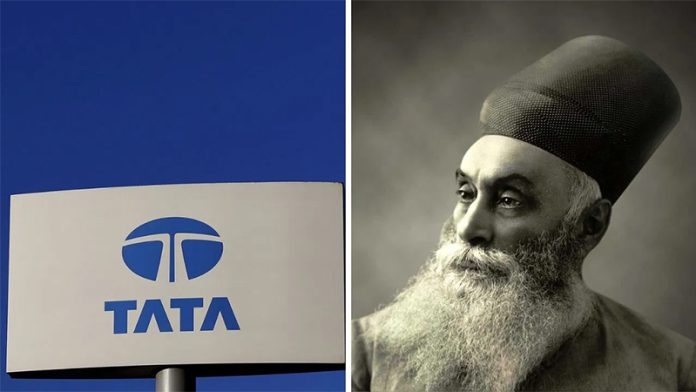

Jamsetji Tata, the founder of the Tata Group, made a strategic choice in the 1890s to shut down the Tata Shipping Line, demonstrating his willingness to exit from unviable ventures. This tough decision was driven by his effort to break the monopoly of the English P.&O. shipping line that dominated exports from India during the 1880s and 1890s, charging high freight rates and favoring British and Jewish firms.

Jamsetji Tata’s textile business suffered due to P.&O.’s exorbitant freight rates and discriminatory practices. Determined to challenge this, he traveled to Japan to collaborate with Nippon Yusen Kaisha (NYK), the largest shipping line in Japan. NYK agreed to partner with Jamsetji, provided he took equal risks and managed the ships himself. To launch the ‘Tata Line,’ he chartered an English ship named ‘Annie Barrow’ at a fixed rate of 1,050 pounds per month, marking the first venture bearing .

Believing the Tata Line would lower freight rates for the entire Indian textile industry, Jamsetji set the rates at Rs 12 per tonne, compared to P.&O.’s Rs 19 per tonne. Soon after, he chartered a second ship, ‘Lindisfarne.’ His efforts received praise, with The Tribune newspaper commenting in October 1894 that it had “been the subject of general praise in the industrial centre of India.”

However, P.&O. countered aggressively, slashing rates to Rs 1.8 per ton but requiring merchants to agree not to use the Tata Line or NYK ships. They also offered some merchants free passage for their cotton to Japan and started a smear campaign against the Tata Line, questioning the seaworthiness of ‘Lindisfarne.’

Jamsetji’s complaints to the British Indian government about P.&O.’s unfair practices went unheard. Over time, Indian merchants withdrew from Tata Line, heeding Jamsetji’s warnings that P.&O. would hike rates once again if his venture failed. The battle spilled into newspapers, with anonymous letters questioning Jamsetji’s “patriotic motives in starting the Tata Line.”

Despite investing over Rs 1 lakh in Tata Line and incurring monthly losses of tens of thousands of rupees, Jamsetji remained steadfast. However, upon reflection, he concluded that there was no sustainable or feasible path forward for Tata Line, given the unfair monopoly supported by the government.

“At the end of this strategic reflection, he appears to have reached the conclusion that there was no sustainable or feasible way forward for Tata Line.”

In a decisive and clinical move, Jamsetji shut down the Tata Line, returning the leased ships to England. This decision, although painful, showcased his ability to make strategic choices unswayed by emotions.

“He sent back to England the ships he had leased, and the Tata Line was, sadly, shut down.”

Jamsetji Tata’s ventures such as Empress Mills, Svadeshi Mills, Ahmedabad Advance Mills, Tata Steel, and Tata Power were successful. The Tata Line, however, did not achieve the same fate.

“The story of this venture, Jamsetji’s initial vision as well as his decision to exit from it when he saw no ray of hope, as the industry was dominated by an unfair monopoly strongly supported by the then government, tells us that he did not shy away from making the right strategic choices untainted by emotions.”

The book, ‘Jamsetji Tata – Powerful Learnings For Corporate Success’ by R Gopalakrishnan and Harish Bhat, chronicles this period, illustrating Jamsetji’s resilience and strategic acumen in the face of overwhelming challenges.